Among the Aviators: A Day at the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome

The biplane’s eight-cylinder engine roars into life and we head to the start of the runway, a grass field surrounded on all sides by a canopy of summer foliage. I am sitting on the wooden bench that serves as a seat inside the cockpit of a 1929 New Standard D-25 “Barnstormer.” The pilot revs up the engine and the old plane gathers speed.

The single-propeller craft moves along the grass of the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome with the jaunty bounce of a Roaring Twenties aristocrat, and in no time at all, we are airborne, rising effortlessly into the clear blue sky of a hot summer afternoon. As we skitter through the air, the biplane’s black fuselage shines in the sunlight, and I gaze down on the verdant forest and farmland that tracks to the Hudson River.

The young woman piloting the biplane beams me a confident smile and then banks the plane sharply. We turn in tight loops, the plane tipped left at an acute angle, as I see far below me the shimmering surface of the Hudson. The whole thing is exhilarating, and I can sense what it must have been like for those early aviators, intoxicated by this new form of travel.

The D-25 was built in the Golden Age of Aviation when crowds flocked to see daredevil pilots demonstrate the new miracle of flight at rural air shows staged around the country. The planes were nicknamed “barnstormers” because the air shows they performed at often took place in farmers’ fields. The pilots, meanwhile, were usually veterans of the First World War who astounded crowds with recreations of aerial battles and feats like “wing walking.”

Riding in an old biplane, you get to re-experience the wonder of those early crowds as you come face-to-face with the sheer precariousness of early flight. You see viscerally that the plane’s body–all that protects you from a sky fall of 1,000 feet–is no more than a thin coating of aluminum alloys, held together with wood, wire and fabric.

Meanwhile, the engine that is powering the adventure is only a few feet ahead of where you sit, and when you raise your phone to take a selfie, it’s nearly torn from your grip by the force of the plane’s forward momentum. How on Earth is this even possible? You may wonder—as those early onlookers must have wondered, too—as they looked up to see those magnificent men in their flying machines describe arcs, twists and loop-the-loops in the skies of interwar America.

Of course, it wasn’t just magnificent men. Amelia Earhart is one of the most famous cultural figures from the era of early flight, making history as the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean in 1932. The young woman at the helm of the D-25 I ride in, Emma Crawford, is 24, one year older than Earhart was when she first found her calling as a pilot. Crawford’s interest in planes, by contrast, has been lifelong – spurred on by an aviation mechanic father, she got her pilot’s license when she was only eighteen. “Flying is all I’ve ever really known,” she tells me, when we are safely back on terra firma. I ask her why she likes old planes in particular. She says it’s partly for the challenge; with barely any instrumentation compared to modern aircraft, the flying experience is far more hands-on, she says. More than that, though, “It’s the romance of it all,” says Emma. “In an overly complicated world, it’s a simplified version of life.”

At Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, you feel yourself transported back to simpler times. Besides the biplane rides, The Aerodrome hosts weekend airshows throughout the summer whose format has remained largely the same since they were begun in the late 1960s. “The Saturday show chronicles the history of flight, and the Sunday show showcases our First World War planes,” says Tara Grieb, The Aerodrome director.

Tara has worked at The Aerodrome since the 1990s, starting her career here as a teenager, performing in the weekend air shows. In the museum, I chat with Tom, a volunteer who is busy cleaning up a 1:6 scale replica of a Howard DGA aircraft. Like Tara, Tom’s association with The Aerodrome goes back to childhood. To the soundtrack of Jazz Age tunes playing from an unseen speaker, Tom tells me how he came to The Aerodrome for the first time in the 1970s, beginning a lifelong infatuation that would lead him to eventually relocate to the Hudson Valley.

During those early visits, The Aerodrome was still run by Cole Palen, the larger-than-life aviation enthusiast who started Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome. Tom recalls that Palen, a World War II veteran, was his childhood hero. “He would talk to me sometimes, but I was too shy to say anything back.”

Palen founded The Aerodrome after discovering a small collection of disassembled First World War aircraft in a disused hangar at the Roosevelt Field airport on Long Island. Famed as being the place where Charles Lindbergh took off for his historic transatlantic flight.

When the airfield closed a few years later to make way for a shopping center, Palen used his life savings to buy some of the vintage planes and relocate them to his family’s chicken farm near Wappingers Falls. He began restoring the aircraft and flying them in the skies above Dutchess County, eventually setting up The Aerodrome on an old farm he bought near Rhinebeck in 1959.

Inspired by Palen’s passion, other preservationists of early flight were drawn to the nascent aerodrome, which expanded in time to become a world-renowned living museum of aviation history, with its carefully choreographed airshows pulling in thousands of visitors each weekend. Palen, who died in 1993, was “a hero worthy of being called a hero,” says Tom.

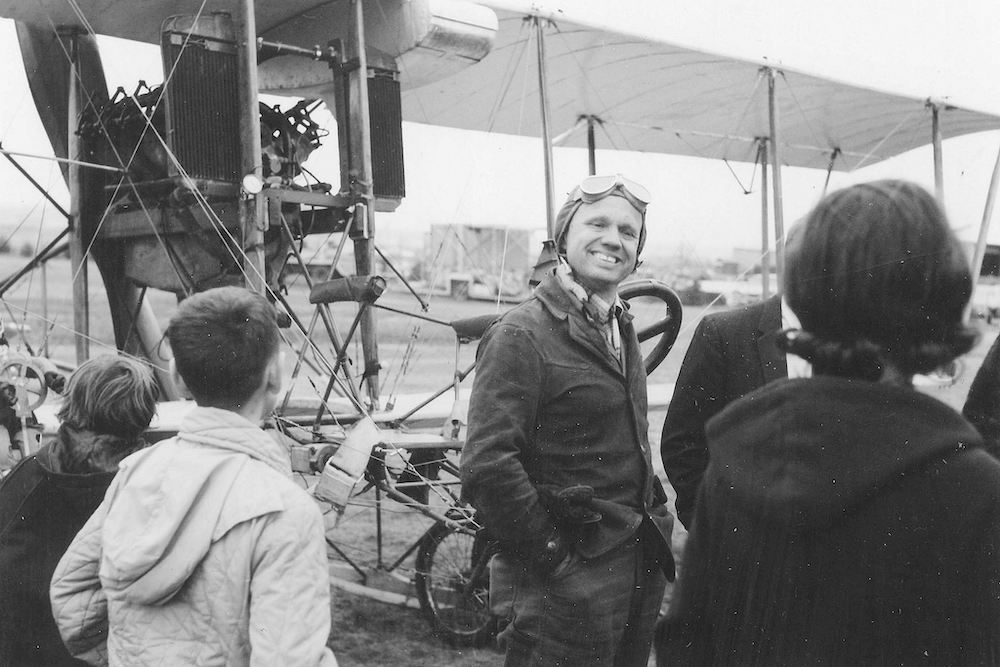

Founder Cole Palen | Photo by John Wallace Hartford

The Aerodrome Museum is housed across four buildings, three of them aircraft hangars containing original and replica aircraft charting the history of aviation from its pioneering days in the early 20th century through World War One to its heyday ending around 1940.

The museum collection is exhaustive, containing early aviation rarities like reproductions of the Wright Brothers’ 1902 Glider, the first heavier-than-air craft to contain a mechanical control system, and a replica of the Demoiselle, a 1909 flying machine made from bamboo by the Brazilian aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont.

But it was Palen’s conviction that a plane was not really a plane unless it could fly. And so the real joy of a visit to Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome is the opportunity to see its historic collection take to the skies. A short time after my biplane ride, the Sunday airshow begins.

Old Rhinebeck’s unique collection of pre-war planes is introduced to the crowd, mostly made up of families, through a slapstick storyline involving a love triangle that includes an evil baron flying a Fokker D-6 fighter plane. All the characters are dressed in period costumes and drive around The Aerodrome in pre-war cars, including an original Ford Model T, the first mass-produced automobile.

A French fighter pilot crops up in the story too, a chance to showcase the SPAD S.XIII, a biplane developed by the French military and flown also by U.S. Air Force pilots in the skies of northern Europe during the Great War.

Next up comes the Curtiss “Jenny,” a well-known U.S. biplane developed as a training craft for WWI fighter pilots. Since Jenny was sold off cheaply after the war to the veteran pilots who started the barnstorming phenomenon, it was also the first plane most Americans back then would have seen.

Sandwiched between the war planes, the crowd is treated to a short flight by a pioneer plane, the Curtiss Model D. Made in 1911, the plane’s bizarre design was the brainchild of aviation pioneer and Curtiss aircraft founder Glenn Curtiss. Known as a “pusher,” the plane was configured to seat the pilot at the very front of the plane’s body and the propeller at the back.

The pilot controlled the plane through a complex system inspired by Curtiss’ background in motorbike racing, with the pilot expected to lean left and right to maneuver the wing flaps. Since The Aerodrome’s runway is too short for the Model D to clear the tree line, it flies briefly and only at a few feet above the ground. Still, it’s an amazing sight to see this heirloom of aviation history in the air.

The air show winds down and I get myself a hot dog on the way out. The evil baron has been defeated and the lovers reunited, and as the families file past me on their way home, I feel a pang of nostalgia for a time I never lived through but which seemed a simpler, more hopeful era in American history.

It was a time when the possibilities of human endeavor still seemed to mean something; a time when a generation of enthusiasts could come together and do something seemingly impossible and everyone could get excited about it. At Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, they remember this time fondly, and for a few hours on a Sunday afternoon, it’s a pleasure to share in their dreams.

Photos courtesy of Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome + Paul Willis

Follow/Connect with Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome via Website | Facebook | Instagram | Inside+Out Spotlight

Write a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.