In the Studio with Contemporary Artist Andrew Lyght

Today, we are in the studio for an exclusive interview with artist Andrew Lyght. For the Guyana-born, multi-disciplinary artist Andrew Lyght, whose career has spanned continents, mediums, and decades, line is more than a compositional element – it’s a way of life, a visual throughline from childhood kite-flying in South America to geometric abstractions that now fill gallery walls. With an eye honed by years in Montreal, New York City, Rome, and beyond, Lyght continues to “walk the line” between past and present, form and freedom, personal memory and modernist exploration. Now based in Kingston, he enjoys mornings nestled above the Ponckhockie Creek, where he greets each day like he always has – watching the horizon for what beauty and possibility the morning might bring.

Andrew Lyght’s solo exhibition, Touch Wood, opened at the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild’s Kleinert/James Center for the Arts, bringing his visionary practice full circle to the place he now calls home. The exhibition opened with a reception for the artist on Saturday, June 7, through July 20, 2025, at the Kleinert/James Center for the Arts, 36 Tinker Street, Woodstock, NY. Also, an Artists Talk: Seph Rodney in Conversation with Andrew Lyght and Osi Audu, was on June 8th at 2pm.

“Relying on wood construction skills he acquired as an apprentice house framer in his youth growing up in Guyana, Andrew Lyght meticulously builds geometric paintings out of wood, and imbues them with personal abstract hieroglyphs which transcend his purely formal concerns and speak to something of the human condition.” – Curator Osi Audu

In collaboration with Richard Hall and Mimi Young of littlebitcreates, we’re excited to share our exclusive interview with Andrew!

INSIDE+OUT: Where are you originally from, and how did you wind up in the Hudson Valley?

Andrew Lyght: Growing up by the ocean in Georgetown, Guyana, perched on the Northeast Coast of South America facing a vast expanse of sea and sky, I was fascinated by the point where water and sky meet at the horizon and its feeling of limitless distance. To this day, I remain perplexed by that enigmatic phenomenon and how it mirrors pictorial space, as well as the sense of hope and infinite possibility it inspires. It is a fascination that has driven my visual curiosity and practice for over sixty years, exploring the limits of the eye, the formal elements of art, and pictorial space with no fixed boundaries.

I was born in Georgetown, British Guiana, in 1949. In 1966, the country gained its independence and became known as Guyana (which means “Land of many waters”). It is a small tropical country of many rivers wedged between Venezuela, Suriname, and Brazil. Today, it is the only English-speaking country in South America, first settled by the Dutch and then ruled by the English. Guyana, located in South America, has a diverse, multi-racial population comprising East Indians, Black Africans, Native Amerindians, Portuguese, Chinese, and Europeans.

Who or what inspired you to become an artist, and what was your journey?

Andrew Lyght: I was lucky enough to grow up in a neighborhood that was diverse in culture and religion, which has inspired my art making to this day. I started drawing at the age of six, dabbling in watercolor at eight, and won the national junior graphics art competition at ten for portraiture. I scarcely spoke and was extremely shy because of a speech impairment. Observing and drawing was a way for me to process and express what was going on around me in a community of builders of timber and stick-framed houses in what was then British Guiana. In addition to drawing, I spent many afternoons, summer vacations, and weekends working as a builder’s helper, both building and painting houses.

In 1962, at the age of thirteen, I began my formal art training in Renaissance methods as an apprentice to Edward R. Burrowes, Guyana’s leading modern artist, where I learned the fundamentals of art, theory, and practice in drawing, painting, and sculpture in the mid-1960s. During this time, I also spent some weekends working with a neighbor, commercial artist Albert De Freitas, painting Pepsi-Cola billboards and other signs in the city and countryside. At the end of my apprenticeship, my figurative paintings had reached a high level of professionalism, two of which had received national attention. Dancing Rhythm/The Masquerade was purchased by the Guyanese government and given as a statehood gift to Antigua. Fishermen by Night, also purchased by the government, was exhibited at EXPO 67 in Montreal, Canada. I was one of the artists represented in the Barbados-Guyana pavilion at the international event that featured 90 pavilions from countries around the world.

The Year 1968 represented a high point in my artistic development in Guyana. At the age of 19, I was awarded two of Guyana’s top art awards in painting: the International Human Rights Year Award and the Burnham Art Medal (Prime Minister’s Award) for Painting, which earned me the top art prize, the Burnham Gold Medal for Painting. This resulted in my award-winning painting being later sent to represent Guyana in the 11th São Paulo Biennial in Brazil in 1971. That same year, I met Mr. Edward Cohen from Montreal, Canada, who was visiting my uncle, a seaman, who happened to see my artwork hanging in my family’s house. Impressed with what he saw, he encouraged me to travel to further my studies and extended an open invitation for me to visit Montreal, Canada.

I arrived in Canada in late August 1969. That fall, through Mr. Cohen, I was given a scholarship, and I registered for painting and sculpture at the Saidye Bronfman Centre. That same year, I began a series of geometric hard-edge paintings and had my first solo show in North America in 1974 at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, followed by an installation exhibition in 1976 at Vehicule Art Inc. Canada’s first-run gallery – established in 1973. During that time, I received several small grants from the Canadian Council for the Arts. I worked nights and painted during the day.

In 1977, after a few events in my loft space in downtown Montreal, I decided it was time to move to New York City. After having all my large-scale paintings, art books, tools and equipment packed up and put in storage in Montreal, I hopped a bus for New York, arriving at the Port Authority with US$150 in my pocket, a knapsack on my back, and a single artwork made of rusted canvas, string and bamboo structure that folded into a portable case.

In the beginning, I stayed with friends, then the late composer Ed Bland and his wife, Mary Batten, writer of science books for children and adults, introduced me to filmmaker and art impresario Emile de Antonio. De Antonio, in turn, introduced me to Frank Stella and art historian and critic Barbara Rose, who helped me secure a studio at MoMA PS1. I stayed at PS1 from 1978 to 1980, and after completing my two-year residency, Leo Castelli, one of America’s preeminent art dealers of the twentieth century, helped me obtain a special green card that allowed me to live and work in the United States. I then began working in large industrial spaces that I renovated, a 5,000 sq. ft. loft where I lived and worked in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, from 1980 to 1990, followed by an 8,000 sq. ft. loft that I renovated for living, working studio, and ArtSpace, Unfinished in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, from 1990 to 2005. Unfinished exhibited the work of local and international artists from 1996 to 1998.

In 2004, I lost my six-year court battle with the new owners of the Greenport loft building as the rapid gentrification and re-zoning of Brooklyn took hold. At the same time, I was awarded one of the first prestigious artist grants from the Barnett and Annalee Newman Foundation. After a negotiated settlement, I agreed to give up my loft in mid-2005. I spent ten months documenting individual artworks, dismantling fixtures, and packing up my life into crates. I purchased three 20-foot shipping containers to store the entirety of my life’s inventory—artworks, art books, tools, equipment, and household items — and set up a long-term storage arrangement with a friend, Yoav Shapiro, on his property in Vermont.

With my life’s work safely in deep storage. I had reinvented myself, so I began teaching myself how to create 3-D drawings using CAD software and then incorporated digital photographs with them. It seemed like a perfect way to keep making art on my laptop computer for life on the road, and while couch surfing at friends. In the late summer, I left for the American Academy in Rome for a three-month residency in their Visiting Artists/Scholars program. At the end of my residency, I stayed in Europe for a few more months, returning in Spring 2006 and temporarily moved to the Hudson Valley to oversee the renovation of a fellow artist and friend’s 1870 brick Italianate building in the Ponckhockie section of Kingston, New York.

Between 2006 and 2009, I floated between New York City, Kingston and the state of Virginia. Working digitally and having my studio on a laptop computer gave me the freedom to move around without a permanent base. In the summer of 2009 I attended an opening at Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild’s Kleinert/James Center for Arts for Drawing and Prints of Martin Puryear where I met artist Ben Wigfall, a co-founder of Communication Village in Ponckhockie section of Kingston in 1970s and 1980s as a neighborhood facility for local kids that offered art classes, artist talks, and exhibitions and encouraged kids to document both the people of the community, their histories and life in the neighborhood before closing in 1989.

Boarded up for more than 20 years, the distinctive brick 1830 mule barn in Ponckhockie had a long list of potential buyers, at least two dozen. Not long after I expressed interest in it, Ben offered it to me a few weeks later. In the fall of 2010, I was able to purchase it with the help of four friends and a grant award from the Adolph & Gottlieb Foundation. Over the next two years, I labored during the day, stripping the building back to its bare brick shell, leaving only the original chestnut wood hayloft on the second floor. At night, I drafted plans for my new home and studio. With a building permit in hand and my architectural drawing, I rebuilt the building’s interior, completing it in the summer of 2013. After moving all of my life’s work out of deep storage in Vermont, I then settled into my new home, studio and life in the Hudson Valley, returning to art making and to prepare for my 2016 retrospective, Full Circle, at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art in New Paltz. Today, I am a citizen of the United States of America, Canada, and Guyana.

As a multidisciplinary artist working across drawing, painting, sculpture, and installation, how do you choose which medium to use for a particular idea?

Andrew Lyght: I choose to work across this broad array of disciplines because my art training taught me to be a keen observer of life around me and in my travels across many borders. Line is the key visual element and component in all the artwork I create. I often employ line in a variety of ways – conceptually, graphically, and spatially, singularly or in multiple ways within a single work of art.

I was drawn to the element of the line early in my life as a form of survival in a world that seemed out of reach to me verbally, by interacting with it by visual means, making a fishing line to catch fish in the canal behind my house, placing a long plank of timber across the canal to cross, or stepping onto or off a plank to enter or exiting a boat after spending time after school with my uncle, a seaman on a local wharf. Later, I learned from working in the building trades about “dropping a line” or “pulling a line,” working as a builder’s helper and later as a construction worker in New York City.

As a kid, I first learned about “walking line” after a day of kitemaking and flying my kite in a field near home. Walking home with my kite in the air, I became very skilled at throwing a one-foot stick wound with many yards of string over live electrical lines, one by one, and catching it on the other side. Even then, we called it “walking line” through the streets of my neighborhood just to tie the kite off on the porch for the night, leaving it in the sky overnight and carefully taking it down at sunrise. “Walking Line” was considered an art form and a skill young boys strived to perfect.

In 1976, while creating an installation for Vehicule Art Inc., an ArtSpace in downtown Montreal, I started to explore a different form of “walking line” (a method used by builders that employs an imaginary line to calculate the required width of a stair tread to ensure safe passage) by wrapping the gallery with string to make visible the spatial dimensions of the room.

Your work often features vibrant colors and bold geometric shapes. What draws you to these elements, and what role do they play in your creative process?

Andrew Lyght: I began to study the native petroglyphs found on rocks in the interior of Guyana in the library at the home of a British archeologist, Arthur Goodland, whom I met at the Museum of Natural History of Guyana. Before leaving Guyana, I made a series of freehand drawings based on the ancient rock inscriptions in preparation for a series of paintings before leaving for North America. I then drew inspiration from the ancient rock writings, which featured plant and animal shapes, and combined them with the geometric language of modernism to create a new visual language for my own work. I was surprised by the freshness of the results, which then gave me the freedom and inspiration to explore concepts, methods and materials while making art from a wide range of cultures. My use of vibrant colors in my work reflects the colorful environment and landscape that I grew up in Guyana.

You’ve traveled extensively throughout your life — can you share some of the journeys that have been the most meaningful to you, and how those experiences have influenced your artistic work?

Andrew Lyght: I have traveled throughout my life, but it is the visual memories from my childhood that bear the most influence on the artworks that I make, one in which modernist language upholds the Renaissance balance of intellect and passion that I learned from Edward R. Burrowes in Guyana. Recent trips abroad, including a 3-month artist residency at the American Academy in Rome in 2005 and a visit to Dubai, United Arab Emirates, in 2017 for an exhibition of my work, further supported and enhanced that vision.

What are the most challenging and rewarding aspects of being an artist?

Andrew Lyght: For me, the most rewarding aspects of being an artist are getting up at 5 am every day to face the challenges of the day ahead, a habit that began as a child to feed the chickens and then climb to the top of a tropical mango tree to pick fruit before the birds got to it. I still remember those mornings clearly, perched high above the neighborhood during sunrise when the air is quite fresh. Living on the Kingston waterfront in a building that faces the Rondout Creek allows me to observe the first day’s light and the “line” in nature from a third-floor window. Like life, it is an ever-changing landscape. I believe there is no better place to experience it than at home on Catherine Street.

Tell us about the show coming up at the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild, Kleinert/James Center for the Arts.

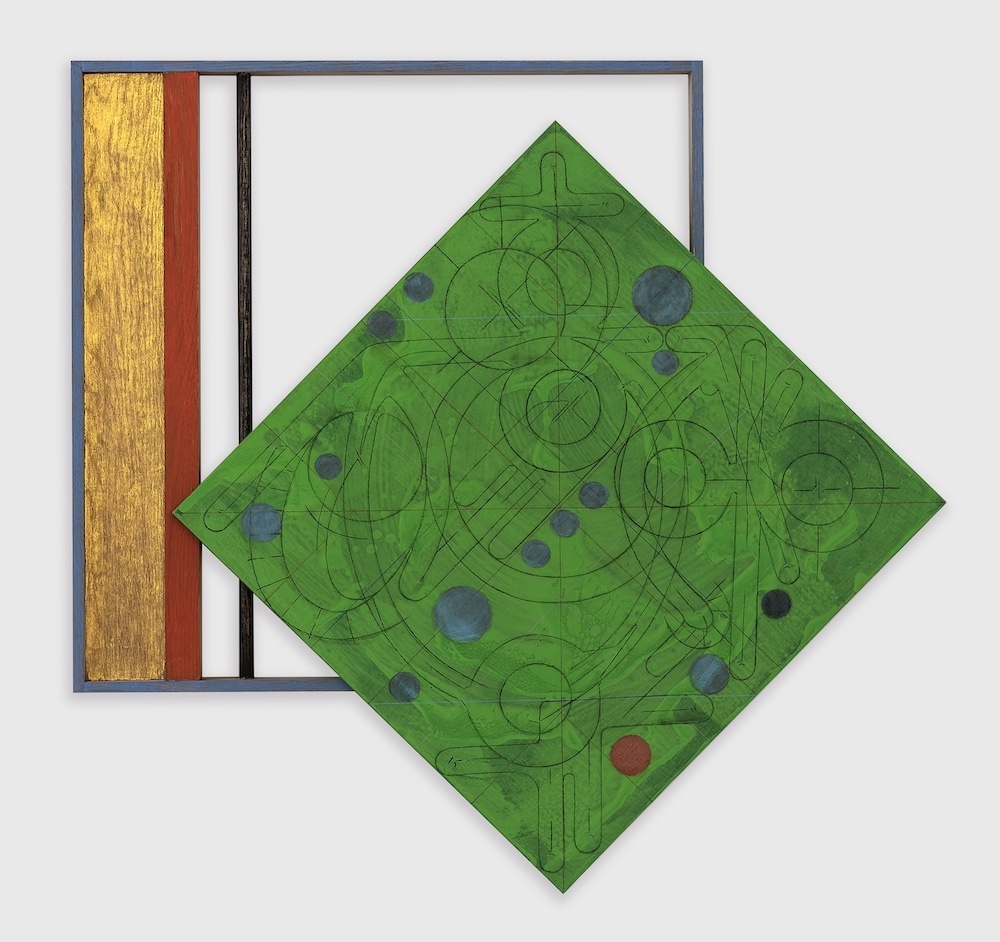

Andrew Lyght: My solo show, entitled Touch Wood, curated by Osi Audu, opens on June 7th at Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild, Kleinert/James Center for the Arts. The work in this exhibition continues my exploration of line. “Walking line,” as in an act of drawing (and a body of my work), is an expression of line over time in all its spatial dimensions. Laying out a composition or a plan, finding and marking the center, involved working off a line, whether on a sheet of paper, plywood, or a length of timber or bamboo. This is how each inquiry typically begins. There will be 12 works of art in the show, including a sampling of earlier works and my latest body of work, Walking Line. The new work focuses on my lifelong visual curiosity of exploring the limits of the eye, the formal elements of art and pictorial space with no fixed boundaries. Walking Line is a system of interchangeable modular units designed to be presented alone or as diptychs. The modular units are built in such a way as to emphasize the way that line operates both graphically, like that of a sign or totem, or spatially, like that of an empty picture frame that delineates a space on a wall.

A description of one of the works in the exhibition, a diptych, is as follows.

On the left side: The placement of a horizontal square beam of wood as a lintel, color-stained on one side with a paint stick to look like a broad brush stroke on the wall. A fine line of cord is then pulled downward by gravity off the center of the lintel. Threaded through a two-dimensional plane, affixed along the length of the cord with a vertical end post held straight by the gravitational force from the mass and weight, creates a plumb line. The flat plane is like a blackboard in suspension, ruled with geometric straight lines on its surface, overlapped with fluid, curvilinear freehand drawings of shapes and forms that are organic and evolving naturally.

On the right side: The dynamic tension between spontaneity and structure, its placement within an open rectangular picture frame is like a window in a wall for the admission of air and light—light that illuminates the graphic and physical characteristics of a network of shell-structures stained with paint stick that reads like a synthesis of lines and simultaneously like a while a built object that frames the space on the wall.

Walking Line has allowed me to continue to toy with the limits of the eye and extend the boundaries of an art form that appears to have no fixed boundaries.

What local businesses do you rely on to be successful?

Andrew Lyght: The local businesses that I rely on to be successful include Woodstock Building Supply, R& F Handmade Paints, Catskill Art Supply for supplies, Monkey Joe’s Roasting Company for morning coffee, Dolce for Saturday breakfast, and for groceries: The Meat Wagon Butchery, Adams Fairacre Farms, and Bread Alone Bakery.

What makes living in the Hudson Valley special for you?

Andrew Lyght: I love making art here in Kingston, New York, far from the maddening crowd and close enough to keep an eye on the rat race in the big city. It is the perfect location with easy access to a train or bus to New York City and the peace and quiet that I need for work in the studio. Sitting high on the third floor and looking out to the beauty and calm of the Ponckhockie Creek waterfront, I am reminded of life in New York City in the 1970s and Brooklyn in the 1980s with few distractions. I miss the old days in the city when creative people had Manhattan and Brooklyn to themselves.

In the Studio photos by Little Bit Creates | Art photos courtesy of Andrew Lyght

Follow/Connect with Andrew Lyght via Instagram

+ + +

See more of our IN THE STUDIO WITH… Artist Series:

In the Studio with Artist Elizabeth Keithline

In the Studio with Bespoke Ceramicist R.A. Pesce

In the Studio with Experiential Artist Amanda Russo Rubman

In the Studio with Multimedia Artist David McIntyre

In the Studio With Artist Olaf Breuning: Laughter in the Dark

In the Studio with Contemporary Artist Andrew Lyght

In the Studio with Mixed Media Artist Yoko Izu

In the Studio with Abstract Artist Joel Longenecker

In the Studio with Horticulturist and Encaustic Artist Allyson Levy

In the Studio with Multidimensional Artist David Kucera

+ + +

This ongoing artist series was produced in collaboration with Richard Hall and Mimi Young, founders of littlebitcreates.

Richard Hall and Mimi Young are the creative forces behind littlebitcreates. They produce a variety of projects, including in-depth artist profiles, event-specific promotional videos, and music videos. Their approach is exciting, innovative, and contemporary. In addition to their client work, Hall and Young collaborate with other creatives to create multidimensional, neo-surreal videos as part of a noncommercial venture. Littlebitcreates emerged from the extensive knowledge Hall and Young gained over 30 years of experience in photo shoots and multimedia art. They exclusively shoot all of their videos on iPhones, appreciating the distinctive aesthetic it produces and the comfort it offers their subjects in front of the camera.

Follow + Connect with littlebitcreates via Website | Vimeo | @littlebitcreates

Write a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.